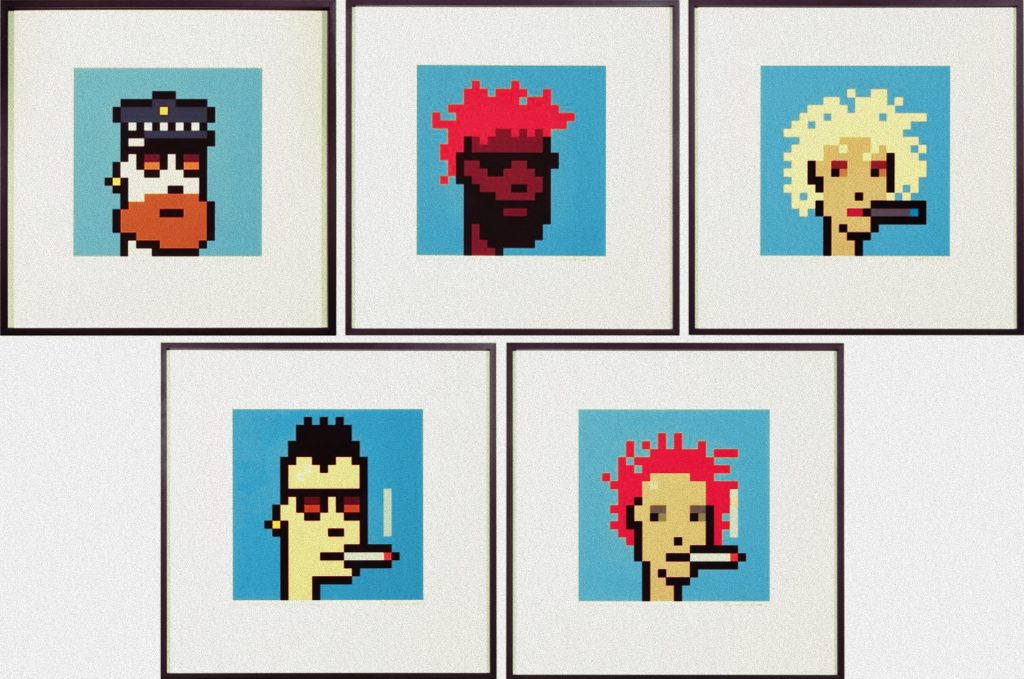

Recently, Sotheby’s made history by auctioning what it called ‘phygital’ artworks for a record price. CryptoPunk pixel-art pieces sold for $11.8 million in a ground-breaking move by the auction house.

“These five fantastically rare ‘phygital’ punks form a very important bridge between the physical and the digital… This is where the digital artworld meets the traditional.” – Sotheby’s, 2021

But ‘phygital’ is a clumsy portmanteau to describe two worlds which cannot be united in the way the word seems to convey: the digital, and the real.

Buyers were actually bidding on two items: the physical print of the CryptoPunk itself, and the NFT, sold as a dual lot.

Part of what makes a CryptoPunk valuable at all is down to the realm in which it exists: notably, Sotheby’s is not attempting to sell CryptoPunks just as physical prints. That would likely end in failure; it is hard to see how those prints would fetch similar amounts to their NFT doppelgangers. But there is an underlying incoherence in trying to transmute the value in one realm to the other. The physical objects already have their value; their private property condition is met simply by existing in only one instance.

The NFT, Sotheby’s explains, relates to just the digital version. And, as I have argued before, it’s as accessible and replicable as any other such work, for which the NFT provides the equivalent private property condition.

But it is interesting that Sotheby’s considers it possible to refer to this amalgamation of two realms by a term like ‘phygital’. For this represents nothing more than the collection of two different kinds of lots. By using this word, Sotheby’s reveals its aim to ‘bridge the gap’ between real and digital art.

By selling one with the other, they are not bringing about a new kind of work – there is nothing here that can possibly achieve any ‘gap-bridging’, any more than selling a Rembrandt and a Bacon together can be called a ‘Rembacon’. Rather, they seek to generate legitimacy for the NFT (already the subject of much criticism) by making a tenuous association between it and the familiar realm of physical art objects.

The longer-term purpose of this is likely to involve a confusing project: can the private property condition of the physical art object be superseded by that of the NFT? There are already spurious whispers among the NFT crowd that, given that blockchain contracts could supersede traditional physical contracts such as house deeds, could NFTs provide a kind of guarantee of ownership of physical art objects too?

Such a move is conceptually worrying, for the consequence is the virtualisation of something already present. It would be tantamount to saying that however well a traditional transaction might appear to function between individuals (‘I give you money for a painting’, for example), the trust involved will always lack the grand objectivity of a blockchain. And therefore, that all transactions decentralised through a blockchain are more ‘trustworthy’ than our usual buying and selling in the physical realm.

This fundamental aspect of human interaction – the determination of ‘authenticity’ – is then given over to something representational. But the abstract realm does not have the kind of objectivity given to us by the physical realm. Rather, the blockchain system is itself a representational construction. Applying it to physical matters constitutes an over-determination of objectivity conditions: it is superfluous. The question is whether use of the blockchain, when attempting to account for physical matters, oversteps an important line and might cause us to grow used to finding value in art only when blockchain-secure. This is in direct opposition to what the blockchain is designed to solve: the problems of virtual matters like digital art, which resulted in the NFT.

However, it is unlikely that the old masters will only be found valuable in the future if accompanied by the requisite NFT: such physical artworks will always be capable of being private property, and the NFT adds nothing to it. Instead, we will probably find that attempts like Sotheby’s, to combine two worlds, are understood as they really should be: attempts to legitimise the world of virtual art and its newly-founded private property condition by association with the longstanding and familiar physical counterpart.

Written by Andrew11.

0 comments on “One of These Things is Not Like the Other”